Graph: Hatchet RJ, et al.

By the bioMérieux Connection Editors

If geography truly is destiny, this saying was never more true than during the influenza pandemic of 1918. Where you lived often determined if you survived, with high fatality rates in large cities, overcrowded military bases, and the congested refugee camps that housed the displaced during World War I.

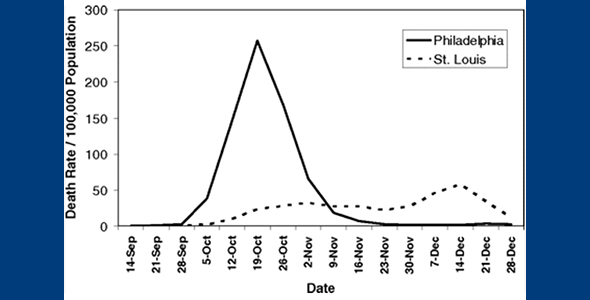

The public health response to the pandemic in Philadelphia and St. Louis differed dramatically, as did the death rates, with Philadelphia having one of the highest rates in the U.S., and St. Louis one of the lowest.

In 1918, Philadelphia had a population of 1.7 million with an additional 300,000 crowded into the city as a result of industrial ramp-up for America’s entry into World War I. At the outset of the pandemic, 75% of Philadelphia’s hospitals’ medical and surgical staffs were overseas for the war.

Influenza first appeared in Philadelphia at the city’s sprawling naval shipyard on September 18, 1918. The following day, over 500 sailors were ill. Hospitals across the city saw a sharp increase in influenza patients on September 19. Ten days later, the city made a fateful decision: despite protests, the city did not cancel a parade for the war effort. On September 28, 200,000 people gathered for the event.

On October 4, there were 636 new cases reported in Philadelphia and 139 deaths. By October 10, over 500 were dead, and panic gripped the city. At the peak of the Philadelphia epidemic, 1,700 died on a single day.

“The contrast of mortality outcomes between Philadelphia and St. Louis is particularly striking,” according to Richard Hatchett, Carter Mecher, and Marc Lipsitch, the authors of Public health interventions and epidemic intensity during the 1918 influenza pandemic.

“The first cases of disease among civilians in Philadelphia were reported on September 17, 1918, but authorities downplayed their significance and allowed large public gatherings, notably a city-wide parade on September 28, 1918, to continue. School closures, bans on public gatherings, and other social distancing interventions were not implemented until October 3, when disease spread had already begun to overwhelm local medical and public health resources.”

While the surge in population and the shortage of doctors and nurses played a role in the death toll in Philadelphia, nearly every major city in the U.S. was contending with these same problems. According to Hatchett et al., the greatest problem in Philadelphia was the absence of leadership needed to curtail the spread of influenza. Their proof? St. Louis.

“In contrast, the first cases of disease among civilians in St. Louis were reported on October 5, and authorities moved rapidly to introduce a broad series of measures designed to promote social distancing, implementing these on October 7. The difference in response times between the two cities (≈14 days, when measured from the first reported cases) represents approximately three to five doubling times for an influenza epidemic. The costs of this delay appear to have been significant; by the time Philadelphia responded, it faced an epidemic considerably larger than the epidemic St. Louis faced.

Philadelphia had a peak weekly excess pneumonia and influenza (P&I) death rate of 257/100,000 and a cumulative excess P&I death rate (CEPID) during the period September 8 – December 28, 1918 of 719/100,000. St. Louis, on the other hand, experienced a peak P&I death rate, while NPIs were in place, of 31/100,000 and had a CEPID during the period September 8 – December 28, 1918 of 347/100,000.”

St. Louis benefited from the leadership of Dr. Max C. Starkloff, Health Commissioner for the city of St. Louis. Like in Philadelphia, the disease first appeared at a military base in St. Louis, the Jefferson Barracks, which was 10 miles from the city. By Oct. 1, a handful of influenza cases were reported at Jefferson Barracks. Within days, the numbers soared to 500.

Starkloff closely monitored these developments and didn’t hesitate to close schools almost immediately. He went on to close factories, theaters and retail outlets. Starkloff faced intense pressure from St. Louis merchants, public school officials and politicians to reopen these facilities, but he refused. Schools were closed for nearly 3 months, as were many other population hubs.

But the citizens of St. Louis benefited from Starkloff’s insistence: “When discussing the history of the tragic 1918 influenza epidemic, St. Louis is often held up as a model city. Because of the quick and sustained action by its leaders, St. Louis experienced one of the lowest excess death rates in the nation, just 358 per 100,000 people.”

Graph: Public health interventions and epidemic intensity during the 1918 influenza pandemic.

Opinions expressed in this article are not necessarily those of bioMérieux, Inc.

I I am astonished at the inept behavior of the President from the start of this crisis. He’s claiming plausible deniability, but he had been told by several entities (specifically created by the White House to study and report to the needed protocols for just this possible event) that action was imminent in 2019. Yet he’s taking credit for a false sense of security, while blaming the same people who pushed for change during the last few administrations for dropping the ball. Webster’s Dictionary should read thusly: Delusional- Donald Trump thinking he is smarter than everyone else in the world even though he’s been proven to be dumber than the average preschooler in the ways of Leadership and Honesty.

In case anyone wants an honest opinion from a regular tax payer who’s family depends on her to support them and keep them safe and healthy(including her disabled spouse). Thank you for your time… it’s fleeting for so many.

A big difference is then it was considered and proven deadly. It has not today. Over 12,000 died in this country alone this year from the flu, vs 26 for the Coronovirus.

The difference is that millions have been infected with the flu this year and you can have a realistic death toll. With Covid-19 there are still no realistic and reliable numbers of how many are infected in the US. Testing is much too slow and underdeveloped. If there were realistic statistics, published openly every day, like in Europe, there would be good arguments to start early with social measures and even shutdowns when necessary.

Deacon John Berstecher – in the 32 days since your last comment, over 20,000 Americans have died. I just wonder if you have changed your mind, or do you still consider coronavirus to be less of an issue than influenza?

Do you feel like a stable genius now? All pandemic starts from ONE (1) patient.

This comment aged like warm milk.

I’m sure you just moved the goalposts.

Thanks for this comparison of the response from two cities and the strong impact of fast reaction and refusal to bow to public pressure in considering when to re-open.

My question: What did people whose business was closed for those three months due for money? Most people live paycheck to paycheck, and can’t miss one week of work – much less twelve!

Also, with very limited “remote work” options, what happened to the businesses themselves? How did people get food?

Finally, while large gatherings and events were not allowed, did people have small gatherings? It’s not like they could stay home and binge watch Netflix for weeks. Thanks!

I know it’s trite to say it, but “Those who forget the past are doomed to repeat it” The highest level of U.S. policy in 2020 is like Philidelphia is 1918