By Chris Cook, PharmD, Ph.D.

Good antibiotic stewardship means treating each patient with the precise antibiotic for their infection and discontinuing their exposure to antibiotics that will not help them, as rapidly as possible. So, there should not be a conflict between using powerful antibiotics when they are needed and avoiding them when another drug will do. The challenge is how to quickly determine which patients really need powerful drugs and which do not. Good antibiotic stewardship is a race against the clock. If patients need those drugs and don’t receive them in a timely manner, it may become too late to help them.

We fear Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) infections the most because carbapenems are our antibiotics of last resort. Once we lose those drugs, our treatment options begin to evaporate. The mortality rates for patients who get invasive CRE infections range from about 30% to 70%.

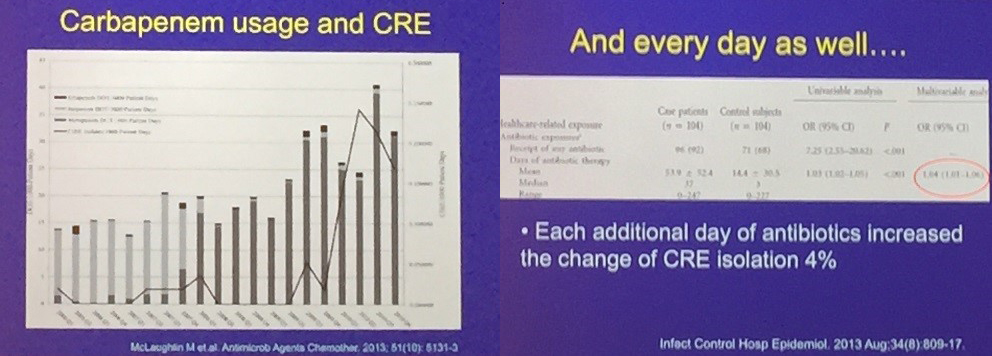

As seen in figure 1, carbapenem use directly leads to carbapenem resistance, so physicians avoid prescribing that antibiotic for good reason. But, as more and more patients have infections that are resistant to our first-line therapies, we’re increasing our use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, such as carbapenems. And by using those drugs, we contribute to the problem of resistance.

Let’s take a step back and look at where resistant microbial infections have the greatest impact: the healthcare setting, hospitals, nursing homes, etc. Patients today live for many years, if not decades after battling cancer. An ever-larger number of people live with donor organs. And, of course, HIV/AIDS is no longer the death sentence it once was.

Nevertheless, those patient populations are vulnerable. Hospitals today have a large population of patients who are very susceptible to all infections and—unlike the healthy—do far worse when infected by resistant organisms.

Perhaps unexpectedly, antibiotic resistant bacteria have one clear disadvantage: they are rarely as virulent as the antibiotic susceptible version of the same strain. But even those less virulent strains pose a potentially lethal threat to our growing population of vulnerable patients.

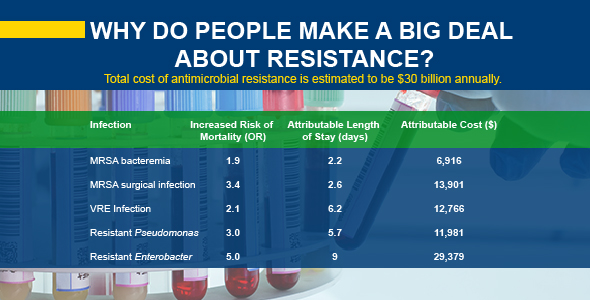

In general, when comparing hospitalized patients who have either an antibiotic resistant or an antibiotic susceptible pathogen, the patients with the resistant version have worse outcomes and double the mortality. If the patient with the resistant infection survives, they’re going to stay in the hospital twice as long. Costs rise dramatically the longer those patients remain in the hospital and unfortunately, so do their chances of picking up another resistant infection within the hospital.

This is a very serious problem. We’re struggling to determine the right balance of antibiotic use in these situations. Of course, we should use carbapenems very judiciously, but by blindly curtailing the use of that class of antibiotics, we could put lives in jeopardy.

So, we’re in a strange situation as stewardship personnel. We must balance the need to find the right drug for the right patient with the need to treat potentially deadly infections as quickly as possible. But determining the correct drug can take time, so as we wait, physicians are trained to save the lives of patients, which means that they will prescribe broad-spectrum antibiotics. Resistance was first identified by Alexander Fleming not long after he discovered the first antibiotic, penicillin, nearly 70 years ago. Yet penicillin is still used today. We can coexist with resistance as long as we keep tight control of it.

First and foremost, we need to fundamentally change our thinking about antibiotics. Antibiotics are not benign compounds that we’re putting into patients. When people say that an extra day or two of antibiotic use doesn’t matter, that’s simply not factual. Every unnecessary antibiotic exposure increases the risk of antibiotic resistance, and it can lead to additional health complications for patients.

Novel antibiotics are vital, but they won’t solve this problem alone. Resistance rates keep rising, and patient outcomes continue to get worse. To counter that, we’re prescribing more broad-spectrum antibiotics, which results in rising resistance rates and worsening outcomes for patients. That same problem will accelerate resistance to new antibiotics as well. Antibiotic stewardship is the only answer to this conundrum.

Opinions expressed in this article are not necessarily those of bioMérieux, Inc.

Christopher Cook, PharmD, Ph.D.

Christopher Cook has over 20 years’ experience in pharmacy practice ranging from academia to clinical practitioner and outcomes researcher. Dr. Cook is currently the Senior Director, Antimicrobial Stewardship Customer Support at bioMérieux, Inc.. He also serves on the National Quality Forum Patient Safety Committee. Prior to joining bioMerieux, Dr. Cook served as a Clinical Professor at the University Of Georgia College Of Pharmacy.