By the bioMérieux Connection Editors

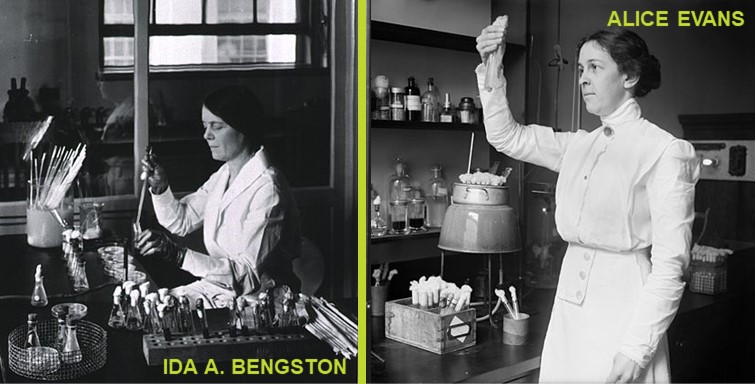

March is Women’s History Month, which aims to observe and celebrate the vital role women have played in American history. bioMérieux Connection takes this opportunity to spotlight two women whose contributions to bacteriology greatly improved public health and paved the way for future women in science.

A Pioneer at the United States Public Health Service

Ida A. Bengston (1881-1952) majored in mathematics and languages at the University of Nebraska and graduated in 1903. Bengston worked as a cataloguer at the U.S. Geological Survey library but was ultimately uninterested in her position and decided to return to school at the University of Chicago, where she earned an M.S. and Ph.D. in bacteriology.

She was hired to work at the Hygienic Laboratory of the United States Public Health Service (USPHS) in 1916—the first female to be employed as a scientist at the lab. Bengston ‘filled her position so ably’ that she paved the way for 10 more women to join the lab over the next two decades. Establishing herself as a stellar employee and one of the country’s leading bacteriologists, the USPHS moved Bengston around the country, wherever her expertise was needed most.

One of Bengston’s first major breakthroughs came early in her career—1917, her second year at the USPHS. Bengston contributed to the discovery that a tetanus outbreak running rampant across the US could be traced back to a batch of contaminated vaccine scarifiers (a cross-shaped instrument which made scratches on the skin to inject the vaccine). After this critical milestone, Bengston continued researching infectious diseases plaguing various communities around the country, including typhus, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Q fever, botulism, and trachoma.

Bengston’s contributions to bacteriology are immeasurable. Highlights from her career include aiding in the development of the typhus vaccine and creating the method still in use for the detection and differentiation of rickettsial diseases (infections spread through ticks, mites, fleas, or lice).

Sound Science Overcomes Skepticism

Alice Evans (1881-1975) taught for four years after high school and then enrolled in a two-year course for rural teachers at Cornell University. At Cornell, she discovered her passion for science and completed a B.S. in bacteriology, later also receiving an M.S. from the University of Wisconsin. Rather than pursuing a doctorate, she chose to research the bacteriology of milk and cheese for the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Throughout her career, Evans had to overcome doubt from both the scientific community and the dairy industry. Her work studying the bacteria of milk led to her groundbreaking research on brucellosis, a then-unnamed bacterial infection that Evans determined could cause remittent fever in humans and spontaneous abortion in animals. She published the results of her research in 1918, which were met with skepticism from researchers, veterinarians, and physicians who did not believe that the pathogens she described could affect both animals and humans.

The adversity didn’t stop there—Evans also warned the dairy industry that milk should be pasteurized to protect human health and safeguard against infectious agents such as Brucella. She was initially scoffed at but continued her research. By the late 1920s, largely due to Evans’ work, brucellosis was accepted as a danger to both farmers and the food supply. Throughout the early 1900s, the US began issuing regulations for milk pasteurization, and the dairy industry reluctantly complied, lowering instances of brucellosis and other infectious diseases. In 1938, milk products were the source of 25% of all food and waterborne illnesses that were traced to sources, but now they account for less than 1%.

In recognition of her contributions to bacteriology, particularly her work on brucellosis, Evans was elected as the first woman president of the Society of American Bacteriologists in 1928 and served until 1945.

Risks Taken to Improve Public Health

Both Bengston and Evans contracted dangerous infectious diseases over their career. While inoculating rats for her research, Bengston was stricken with the endemic typhus fever (she recovered). In 1922, Evans was infected with Brucella and suffered from periodic bouts of brucellosis for the next 20 years.

Bengston and Evans both retired in the mid-1940s, prompting an Associated Press Science reporter to write, “Two heroines of science, whose contributions to medical knowledge are world-famous, are retiring as researchers for the National Institute of Health.” These remarkable bacteriologists put their lives on the line for their research, contributed groundbreaking discoveries, and opened doors for other female scientists—proving to be true defenders of public health.

Opinions expressed in this article are not necessarily those of bioMérieux, Inc.

Image Credits

Alice Evans

National Photo Company Collection, restored by Adam Cuerden, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Ida A. Benston

Unknown photographerWork of the U.S. Government (National Library of Medicine photograph archive), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons