By the bioMérieux Connection Editors

A new strain of the SARS-CoV-2 virus has been identified in the United Kingdom that researchers have found to be substantially more transmissible than previous forms of the virus—up to 70%, according to estimates. Although more contagious, the new variant, called B.1.1.7., does not appear to cause symptoms that are any worse than previous forms. However, the increased transmissibility poses a significant threat to already-strained hospitals and healthcare systems.

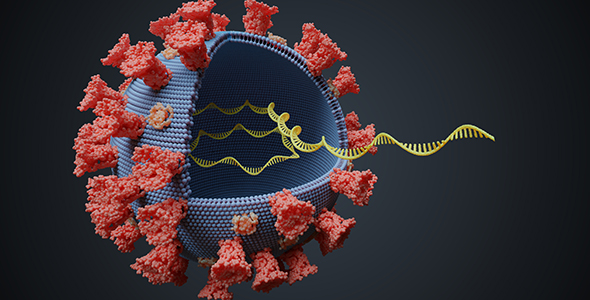

All microbes evolve, so it is no surprise that the SARS-CoV-2 virus is doing so. Researchers in Britain have been tracking the genome of the virus, sequencing up to 10% of new positive samples to look for changes in the virus’s RNA. This critical work is how the new variant was identified. However, Britain’s sequencing only covers the country’s own population. To truly understand how the virus is evolving and the threats such evolution may pose, a much wider effort is needed.

In the United States, for example, there is currently no nation-wide system for regularly sequencing positive samples. Such a surveillance program, “would be able to determine just how widespread the new variant is and help contain emerging hot spots,” according to The New York Times. The CDC’s SARS-CoV-2 Sequencing for Public Health Emergency Response, Epidemiology and Surveillance consortium (SPHERES), has been very helpful, but it doesn’t have a clear mandate and the resources or funding needed to ensure consistent, widespread monitoring. The lack of resources and funding mean that hospitals, academic institutions, and companies have had to finance some sequencing efforts themselves.

Researchers say that the new variant is likely now spreading in the United States, but without robust national surveillance, it is difficult to know the extent. Scientists are in the process of creating new PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) tests that specifically look for the B.1.1.7. variant, but Dr. Nathan Grubaugh, a virologist at Yale University, says that, “It’s overall just a Band-Aid on our lack of having genomic surveillance.”

A national surveillance program, “would not only allow researchers to observe the spread of B.1.1.7., but other, potentially even more dangerous new mutations that emerge in its lineage,” according to The New York Times. Such a system could provide advance warning, allowing public health officials and healthcare workers to plan ahead. With hospitals already overburdened in many parts of the country, that ability would be extremely valuable. Based on the data from genomic surveillance, mitigation measures could be implemented to help reduce the spread of new strains and allocate resources where they will be needed most—and the reduction of negative impacts could be substantial.

Opinions expressed in this article are not necessarily those of bioMérieux, Inc.